Tagged: fiction

Reading Log 2.6.2026

The reason Aristotle should be read and will be rewarding is simple enjoyment of compare/contrast of methods. He also forces you to abandon juhhhhst about every preconception about government and politics you currently hold.

****

GW never disappoints. What a life. I confess that sometimes my mind wanders as the descriptions of all the various messages being sent to and between all the many forts and camps are given. At the same time, what an exciting job, no? Perfect for a young man wishing to prove his worth, I say. What task of today compares with, “Your countryman’s lives depend on you successfully carrying this message through the forest undetected. Can you do it?”?

****

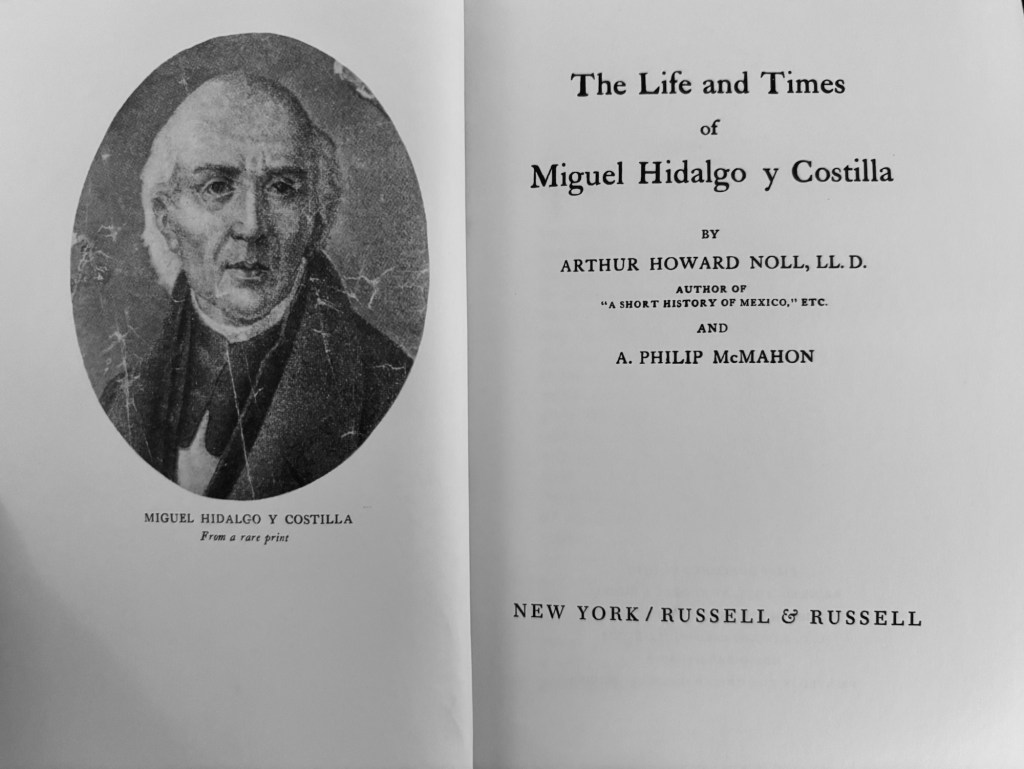

After I discovered Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, after I found a portrait, and after I framed it behind museum quality glass and hung it on my wall, I realized that I didn’t really know much about him or his role in Mexico’s independence. There’s a brief entry in my 1910 Britannica set. And then there’s this book. Suffice it to say, now I do. In short, and probably fortunately, the word “legend” has to be applied. New Spain and the caste system it operated within simply didn’t have an established habit of written record. Another difficulty that can really only be appreciated if you read GW and Hidalgo simultaneously, is the scale of the geography upon which events unfolded. New Spain (future Mexico) was enormous, whereas GW was focused on New York and Long Island and a few other relatively minuscule locations along the Atlantic coast. In the end, however, for both legendary and historically verifiable reasons, Hidalgo does belong among the six men on my wall. Oh, and you’ll never guess the nickname he got after college. So go! Read and learn! (Even the internet won’t help you.)

****

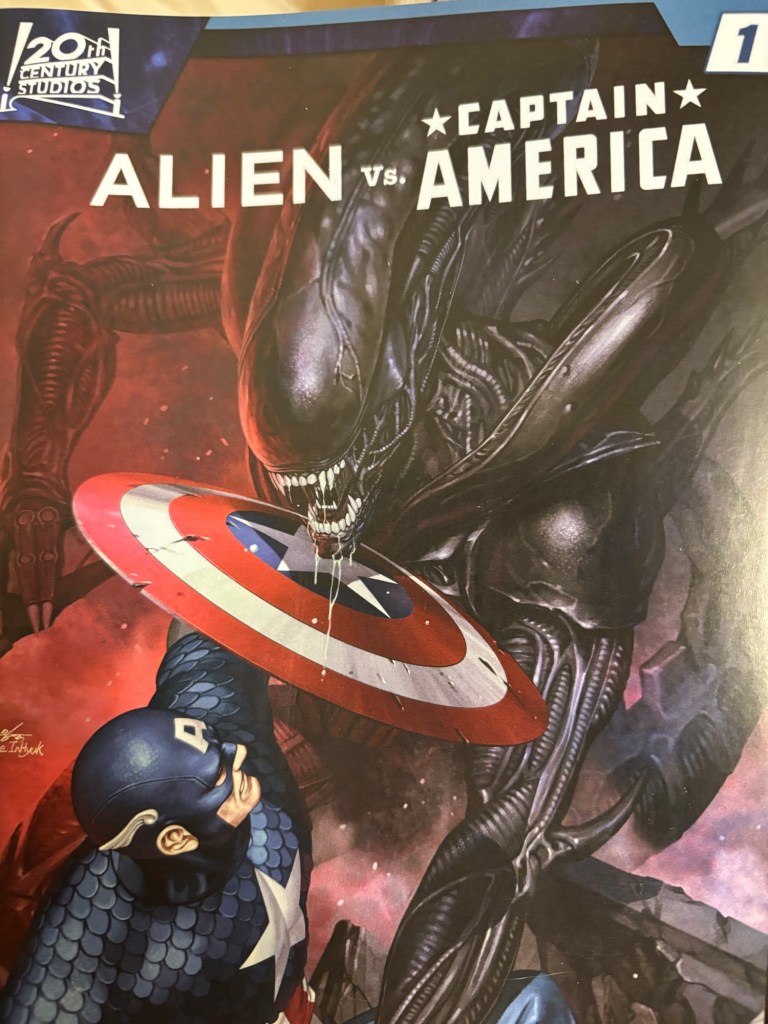

How could I, American hero that I am, not like Alien vs Captain America? Just look at those covers. Rest assured, they do not disappoint.

****

Isaac Newton leads the way for humans—overall. But Aquinas leads the way for methodical writing. This man’s rigid adherence to a method is otherworldly. I won’t say it is commendable, because I am too interested in creative writing. But when I hear people talk and it is utter unfocused confusion, the easy fix is to show them Aquinas.

****

I knew Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. (Read it too.) I did not know about The Mysterious Island. It is fun. A few chapters in and I found myself thinking, “Wait a minute! This is just a genre-establishing sci-fi version of Robinson Crusoe and Swiss Family Robinson.” Then it seemed like it was literally in the next chapter’s opening that Verne, or the narrator, detailed as much and offered a decide-for-yourself-whether-it’s-a meaningful distinction. In any case, compelling start, second act slowed a bit, but the third finished strong. It isn’t a must read. But if you have interest, it won’t disappoint.

Reading Log 4.9.2025

Same for Vol 2 as I said about Vol 1, “Grant’s memoir was amazing and astounding on nearly every level. What a time to have been alive.”

****

Re: Pilgrim’s Progress: I will share the text I sent to a friend.

“On another subject, I finally started John Bunyan’s famous ‘Pilgrim’s Progress’.

Four chapters in and I would say this book may be more valuable to Christianity than the Bible itself. One more entry in the matter of ‘what a shame that folks have dropped it out of vogue’.

If you want a copy, I can send one to you. It is part of our homeschool set.”

(Obviously I would need a GoFundMe account to accomplish this for the world’s population. But if you are serious that all you need is a copy to get you reading, my offer stands. Comment below or email me. We’ll get you one.)

****

I have read tons of Mark Twain. Or it feels like it. But I had no idea about Mr. Wilson and the twins. Twain is ridiculous. I always thought he was hilarious, as evidenced here again, but these open the “ridiculous” description too. And watch out! The “n” word is on full display as he calls into question everything you have ever thought about life on earth.

****

The reason you read Pascal is to see for yourself that these “greats” are impossible to justly or sufficiently summarize. The infamous “wager” is far more involved than how it typically is presented.

****

The math essays don’t teach you particular skills, but they are interesting and do contain such marvelous sentiments, found curiously nowhere else, as, (paraphrasing) “We don’t need to think more. We need to think less. We need to accomplish as much as possible with as little thinking. That is true advancement.”

Oh, and if you want a single essay as an icebreaker, to test the waters, it’s Euler’s hands down. “The Seven Bridges of Königsberg.” See here.

****

I like writing these updates. But I wonder if anyone will ever use them as intended. Time will tell.

My 4-Yr Old Recognized Beauty

She FT’d me as they were walking into the garage to leave for mega-church. The door opened, and the way she holds the camera it was difficult to not notice the barely cloud-speckled blue sky. Then I saw she did too. And without prompting she said, “It’s a beautiful day,” and faded almost into a hum, “in the neighborhood,” which is of course from Daniel the Tiger or whatever the name of the Mr. Roger’s-based show is called. (Not that she has seen it in several months since I tossed the TV, but I feel like being clear that she isn’t an abstract idea floating around in the aether, but a little girl.)

Anyhow, it’s true.

And that’s the point I want to make to all you anxiety-driven, suicide-prone, depression-claimants. Take a look at the lilies of the field. If my four year old can see them, then surely they are there.

The Pathetic Way To Go

They were all in his bedroom.

His brother was the family’s steady anchor, permanently tarred to the deep floor of the ocean of unknown outcomes. He had flown in four years ago, without stopping—without even thinking—to even pack a carry-on. He had stayed bedside throughout the recent wars, throughout the fires, throughout the droughts, throughout the pestilence, throughout the famine. Nothing had moved him; nothing could move him. Nothing would move him. In the four years that had passed, he aged ten. He was worn threadbare. He was balding. He was broke. His wife had left him after the first year. His children hardly knew him. But he was there. And there he seemed destined to remain.

But it was his sister, whose lightest smile always seemed to be returned as though seen through the closed eyes, that wove the siblings together. It was his sister who fed both brothers, his sister who changed the sheets, his sister who replenished the water and flowers of well-wishers, his sister who put on a happy face—indeed never once betrayed an awareness that today wasn’t the best day.

And today, this day of days, was about to be the best day.

His mother and father had arrived last night, cutting short their long-delayed vacation to some distant paradise without hesitation. He was their son. They had only ever left his side, for the first time in years, after finding in his Bible a single page of scripture with a note indicating that “their happiness” was his “heaven”.

All his cousins and aunts and uncles had rushed to be there as soon as word had spread. It had not mattered to any how many planes, trains, boats, or cars it took. No matter the skyways and byways, no matter the cost, they were there.

His wife sobbed and sobbed. Her life was miserable before him and had been perfect with him. She did not know, she could not imagine how she would ever carry on after. So she wept, she cried, she sobbed, she cried, and finally she wept some more. Everyone who knew him and knew of him understood her pain.

The room went silent as his eldest daughter appeared in the doorway. No one could remember the last time he had heard, let alone seen, her. But somehow she knew. Somehow she came. The dim, flickering candlelight revealed the jewelry that had first confused her identity. But when she turned and tossed her backpack aside, the sweet jingle of countless keychains she had affixed, along with the rustle of laminated letters that hung from every zipper confirmed what all were hoping—after so many years away, she came.

His other children were still on their way. The current project that engaged the pair, the world’s two greatest, most creative, most motivated, and most delightful members, had necessitated their delay. In fact, it wasn’t until the world heard and fed the wildfire rumor of the gathering in that room—and for whom and wherefore—that the people pleaded, risking their own detriment by forestalling the work, for the siblings to now travel to where all knew their hearts already lay.

“He’s awake.”

The barely audible whisper was first heard by his sister, as she was handing a fresh coffee to its speaker, her weary, ever so weary, brother—one that never did arrive.

The porcelain mug’s landing on the plush carpet pronounced a soft sound at which his wife, the ever inconsolable and fairest of all to assume that noble title watchman, raised her tear-streaked face. When her fingers rose to wipe all evidence of unhappiness away, the visitors communicated the only news that such action could betray throughout the room as quick as light, yet as soft as feathers.

Right when his brother turned to repeat the announcement, his eyes landed on them. They had just arrived.

“Come! He’s awake!” He repeated as he motioned the children to come and directed the crowd to open a path.

“My dad!” his daughter said, her cheeks uncontrollably wetted with tears of joy.

“Father!” his son declared. Revealing a relationship that transcended time and space—indeed one that could not be rocked by consciousness itself—he added, “We did it! The world is saved.”

Seeing him seeming to make an attempt to raise his head, his brother said, “Rest. It’s no time to exert yourself, good brother.”

“As always, good brother,” our hero began, acknowledging their secret greeting, courageously and with a knowing smirk, one long-since absent and missed, “You’re wrong. It is time; for time is short.” His breathing was burdened with immeasurable truth.

In the history of time, the tides of all oceans had not swelled so much as to fill what all present saw pour forth from this dearest, this loyalist of companion’s eyes. Turning to the room, he cried with exuberance so far only matched by the warming Sun, “He’s right!” he declared. “He’s always right. It’s why I love him.” The very walls joyfully echoed the contagious rapture spread unto all. And then feeling along the bed until his hand touched the familiar, strong, able, and trustworthy hand of childhood, he squeezed with a tenderness not unnoticed by our hero and turned back and said, “You’re right. What would you have us do?”

“Bring her to me.”

At once his oldest now became the focus of the room.

“Help me up, brother. One final time.”

The room gasped as they watched. His mother fainted.

At last he was sitting at the head of the bed. And she was there.

“Da-”

“Shh—” he interrupted, eyes earnestly declaring the sad truth that all were too kind to admit. “Don’t speak. Know that in all these years, wherever your travels took you, I was there too.”

“Oh, daddy,” she cried. “I knew you never abandoned me. I always knew. I just didn’t know how to come home.”

“There, there, my beautiful girl,” he said, bravely keeping his tears at bay.

“I kept everything,” she added suddenly. “It’s all there. Every gift. Every letter. Every book. All the socks. It’s all in the bag. I wanted you to see it.”

As his eyes followed her gesture to the bag she had worn in, the answer to Earth’s oldest question, “Is there anything this man can’t do?” was finally answered. The levy broke. The man couldn’t hide his joy.

(To be continued…)

Goldilocks and the Three Americans

Once upon a time, there was a family of the smallest of sizes, but perfectly intentioned, who lived in a neighborhood-

“That’s not how it goes, Dad!”

“I’m not telling the story we read, A-; I am answering your question about the noises the cameras make.”

“Oh.”

-Whenever these smallest of sizes, but perfectly intentioned, families went out from their house—whether to school or stores or restaurants—they worried about yellow-haired girls who they had heard about when they were children-

“Goldilocks has yellow hair!”

“That’s right, A-. That’s who the noises are supposed to scare aware. You see, Goldilocks is supposed to think, ‘I don’t want to deal with whatever those bears are up to. So I’ll find a house without cameras.’”

“This house doesn’t have cameras!”

“Good eyes, A-. That’s right. If I were Goldilocks, I’d try that house first.”

“You’re not Goldilocks!”

“I know. I’m just answering your question.”

“Oh.”

“You know, A-. I don’t mind sharing with you that besides adding talking cameras to the cornucopian display of my opulent wealth, that story is why I don’t trust any Yellow-Haired women.”

“Look, Daddy!”

“Okay! What? I see a truck.”

“Goldilocks is in that truck!”

“That’s right. I didn’t finish the story.”

-And no one ever saw Goldilocks ever again. But sometimes, when the light is just right, you can see Yellow-Haired women driving white trucks. So if ever on your camera screen you see a white truck in your driveway…hide your porridge!

The Egg Rule

If the yoke breaks, I succumb to my over easy mood.

If the yoke doesn’t break, the desire of my heart was always sunny-side up.

A Moment With My 4 Yr Old

“I’mmmm gonna get you a nap-kin. Cannnn you please be patient?” (delivered in a sing-song manner).

“I’mmm gonna ask Mah-mee.” (answered in kind).

At Bedtime, You Gotta Be Smarter Than The Toddler!

I don’t know why I didn’t think of it earlier.

The trick is having them lay in bed as soon as possible in the bedtime routine. That’s the trick.

I had been reading to them (the best possible thing imaginable). But we had been sitting on the floor together. Or almost together. Usually Bee-bop and Rock-steady would find their way around every corner of the room as if led by a bewitched divining rod while I read and beckoned them back to the fold. But the reading was happening and they even were memorizing the words in turns. So I was fine with it.

But then we would excitedly pray (Aaronic blessing from frame on the wall—“Favor, A-, not favorite”) and sing and then I would put them to bed. Finally, I have a little thing I say to them every night.

But if I left at this point, someone would get out of bed and the light would be on and playing would ensue.

Any parent knows this is enough to drive you crazy. Just GET IN BED!!

No more. Tonight I had a moment of clarity and put them in bed before the book. They both tried to sit up to see the pictures until…they got tired of maintaining that position. Then they laid until the page turn and then sat up and then laid down again after examining the picture.

Finally it was pray, say the thing, and then I sung any remaining pressing ideas to sleep.

Boom!

Lights out.

What an amazing dad I am. And not a moment too soon.

The White Devil

Now the serpent was more crafty than any beast of the field which Yahweh God had made…And the serpent said to the woman, “You surely will not die! For God knows that in the day you eat from it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil.”

“Come on!” he smiled mischievously, “Come on, just tell me. It’s not like we don’t know the nickname. I just want to know it in your language.”

“Oh, no,” the brown mohammedan said, head-shaking, embarrassed and uncomfortable. “It is not right.”

“Seriously, just tell me. How much have we shared with each other so far? I only want to know it to make people laugh. It’s not like I mean any harm to anyone. It would make me betam yetek’eburu if I could whip out that phrase when appropriate. Ehbakahin? Please?”

The mooslims are different in this respect. They are Old Testament in their belief in the power of utterances. The man wouldn’t budge.

“Oh well. Here comes another,” he said to himself. “Hey!” Pointing back down the hall towards the man he just left, the same smile still on his face, he said, “Abdi there won’t tell me how to say White Devil. How about you? I need it for purely social reasons. Please?”

Stonewalled again, and this time by a Christian no less.

That was six years ago.

Today, he knows the real meaning of White Devil. He had always assumed it had to do with brown people being more “spiritual” on the whole and white people being less “spiritual” on the whole. There also was the ever present, at least in recent centuries, technological advantages inherent to the (renowned as white) West that surely must have bedazzled outsiders into believing them to be derived from the dark arts.

Wrong on both points.

His own culture lauds literacy and learning. The greatest shame is an unexpected and unavoidable public display of illiteracy. If one can’t read, they hide that fact from everyone—and if it happens that they come to a moment when they decide to learn, upon taking that step, the choirs of the West rejoice more joyfully than the heavenly hosts when a new believer is baptized. Who, then, wouldn’t want to learn how to read?

But that is the White Devil describing itself, the White Devil marveling at its reflection in precious stones. As described by illiterate cultures, the ones who are lauded today for having “oral histories”, the White Devil is the absolutely ignorant and unfounded fear of what these cultures do not yet understand.

The truly ignorant are not the West’s unwanted newborns put outside to die by exposure like our own illiterate, no. He now sees that the truly ignorant are Adam and Eve, shortly after getting the boot from the garden. They know something is different. They know there is another power. They know they don’t have the power. And like Adam and Eve, they conclude those that do possess the power must be the enemy, the adversary, ha-satan. Or, plainly, the White Devil. And the only idea that populates the uninhabited landscape of their brain is to tell their children the story of the crafty serpent.

A Woman in 1899, Another in 1920, and One from 2024

Self-satisfaction begins with reading a variety of books. This morning, already, I have read from F Scott Fitzgerald’s This Side of Paradise and Jack London’s short story “The White Silence.”

The necessary vital stats of these two giants for this post include London’s work preceding Fitzgerald’s by about 30 years; oh, and London wrote about life in the wild, whereas Fitzgerald wrote about life in, what later would be called, the concrete jungle—the city, specifically high society.

In writing about “life”, they also wrote about women. Women are everywhere, it seems. And not to be avoided.

In order of my reading today, here is a blurb from F Scott on women.

“I’ve got an adjective that just fits you.” This was one of his favorite starts—he seldom had a word in mind, but it was a curiosity provoker, and he could always produce something complimentary if he got in a tight corner.

“Oh—what?” Isabelle’s face was a study in enraptured curiosity.

And, now for the real test, from 30 years earlier and a world away, Jack London’s entry on women.

“Yes, Ruth,” continued her husband, having recourse to the macaronic jargon in which it was alone possible for them to understand each other; “wait until we clean up and pull for the Outside. We’ll take the White Man’s canoe and go to the Salt Water. Yes, bad water, rough water—great mountains dance up and down all the time. And so big, so far, so far away—you travel ten sleep, twenty sleep, forty sleep”—he graphically enumerated the days on his fingers—“all the time water, bad water. Then you come to great village, plenty people, just the same mosquitoes next summer. Wigwams oh, so high—ten, twenty pines. Hi-yu skookum!”

He paused impotently, cast an appealing glance at Malemute Kid, then laboriously placed twenty pines, end on end, by sign language. Malemute Kid smiled with cheery cynicism; but Ruth’s eyes were wide with wonder, and with pleasure; for she half believed he was joking, and such condescension pleased her poor woman’s heart.

“And then you step into a—a box, and pouf! up you go.” He tossed his empty cup in the air by way of illustration and. As he deftly caught it, cried: “And biff! down you come. Oh, great medicine men! You go Fort Yukon, I go Arctic City—twenty five sleep—big string, all the time—I catch him string—I say, ‘Hello, Ruth! How are ye?’—and you say, ‘Is that my good husband?’—and I say, ‘Yes’—and you say, ‘No can bake good bread, no more soda’—then I say, ‘Look in cache, under flour; good-by.’ You look and catch plenty soda. All the time you Fort Yukon, me Arctic City. Hi-yu medicine man!”

Ruth smiled so ingenuously at the fairy story that both men burst into laughter. A row among the dogs cut short the wonders of the Outside, and by the time the snarling combatants were separated, she had lashed the sleds and all was ready for the trail.

I know, I know. Way more from London. But it’s to serve a point, my point.

The earlier-dated passage from London required more words as the task before him included also announcing the different cultures.

But they both offer the same comment—and oh, how detestable the situation!

They both convey a man telling a fairy tale to their woman, and they both convey that women are beholden to men.

We are now one hundred years from F Scott and this question is, by my thinking, the pre-eminent question of our time. My generation has no other issue of more importance on the docket.

And for my part, I have determined resolution of the question. This will not shock regular readers.

I can put the matter in one of two ways, a kind of “glass is half-full” version and a kind of “glass is half-empty” version.

Half-empty: Women are no longer beholden to men. And without men, women are actively disintegrating civilization.

Half-full: Wise women would do well to choose to live as if beholden to men, regardless the true nature of their plight.

****

For the record, Ruth is infinitely more attractive to me. According to the text, she displays taking “pleasure” and “ smiles ingenuously.” (Look it up, if you don’t know. I had to.) She also lashed the sleds.

What did Isabelle do? Nothing that an animal in heat couldn’t.