Tagged: grammar

The Answer to, “What ‘Gender’ means?” A Question Posed by My PhD Candidate Friend

For posterity.

I have to tell a story because I cannot see how the plain didactic situation will help given that you haven’t seen it yet.

I had a friend who was a math professor and he was adamant about Free Market economics. Once he gave me a link to his “behind paywall”guru—a link to one of those YouTube clips that can only be viewed if you have the link, which follows the overall belief he held that humans should pay for valuable things/ideas.

In the clip, the guru/astrophysicist-teacher-dude said, “Every word should have one and only one meaning.” That caught my attention because it is so asinine. The idea that words should be like numbers or math symbols is just ludicrous. To set that as a goal is ludicrous. Immediately questions like, “Which language would these ‘one meaning only’ words be in?” came to mind.

With me?

This relates to gender because language is where gender starts. There are languages (Hebrew and Greek among myriad others) which, when spoken, seem to add or subtract little suffix sounds (like ee or ish) to what we would call pretty much any non-verbs—so nouns, adjectives, prepositions etc. If I were to do this in English, it might sound like, “Hey, Matt! Throw her the ball-ee. And then, Jill, throw Matt the ball. Then, Matt, when you get the ball back, see those girls over there? Throw the ball-ee–ish to them.” (In this example, ee is female and ish is plural).

Why did these sounds develop? Who knows.

But anyone, including you, who would have been looking at or listening to the language(s) would be inclined to recognize (or be taught) that the “ball” part of the sound is the same concrete item and word, but the suffix sound (or lack thereof) changes depending on whether a female is involved.

The catch, of course, is that the method isn’t 1-to-1; in other words, there are exceptions to the rule. But the rule still comes to our minds. So words (aloud and written—many of earliest languages were merely copying the sounds, no such thing as proper spelling existed) became known as the idea…drumroll…GENDER!!

What should humans have done? Is the idea/object behind the word “ball” and “ball-ee” the same thing? Or not? I suppose you could argue that they are two different things. But that seems overly complex. In the end, there is one ball. But for some reason, when it is thrown to a human with boobs and a va-jay-jay, it is called “ball-ee” (in my example).

Next, fast forward through history until the last century and (I am very earnest and serious here; I have come across other folks who admit the following too) we come to the point where this concept of math symbols (think x and y and π), with their one and only one meaning, are thought of as superior to all the often unclear complications of ordinary language. In short, instead of written language copying sounds, people wanted language to represent ideas and with exactness.

HERE IS THE JUMP/CONNECTION: One day someone suggests the idea that biological sex (penis vs vagina) is irrelevant. But they immediately confuse everyone listening because the honest response is, “How can I not be a woman/man?” So these people borrow the grammar category (abstract label) “gender” and apply it to their (NEW) idea. (The idea being that the concrete reality of your biological sex is ultimately irrelevant.)

I offer for your consideration, that even you, friend, must be able to use the word gender when you communicate, both to show you understand grammar, AND to show you understand what time you are living in. There is an idea, however incorrect, called gender now. This is no different than, say, how the ideas psychology and communism are relatively new to the passing scene.

Put in dictionary style, gender (in the context of “ethnicity, class, and gender”) is the IDEA that biological sex is ultimately irrelevant.

The Answer to This Gen Xer’s Middle-School Question, “What Is the Point of Diagramming Sentences?”

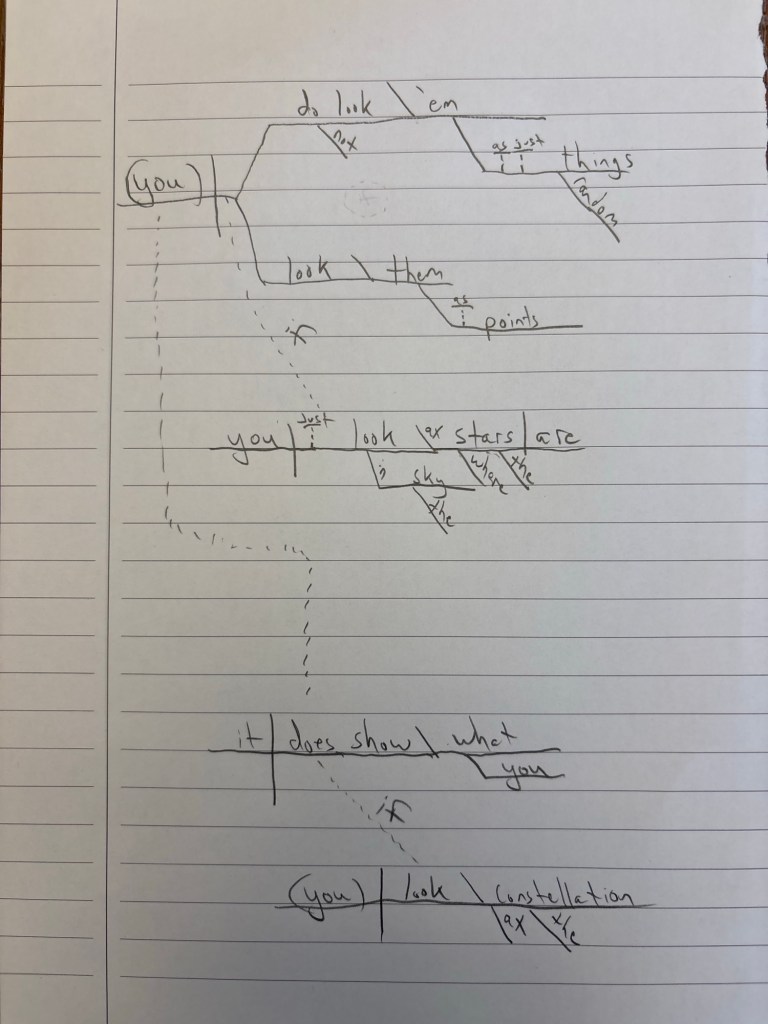

Harris answered, “If you just look at where the stars are in the sky don’t look ‘em as just random things if you just look at them as points look at the constellation what does it show you?”

Before you review the provided diagram, please take a moment to consider the concept she asserted that the “stars” are “random things” and “points”.

That took about 45 min and some help from the internet. Overall, I learned that Harris used the imperative (I hate being bossed) and uncommonly deep subordinate phrasing.

Now, if only we knew what those random points in the sky when it is dark were, then we might be getting somewhere towards understanding Trump’s racism.

Harris 2024!!

Serious Question About Citation Conventions in 2021

No joke, I’m really struggling here.

I want to unite with you and all others who support the unity that Biden just called for. But I don’t know if I should say, A. “Gosh. I got goose pimples when Biden quoted Abraham Lincoln, who apparently said, ‘something something ‘my whole soul is in it’?” (Which of course will appeal to blacks on two levels: firstly, they were freed from slavery by the Lincoln, secondly, they only know a few words like, “soul”, “brother”, and “sister”.)

Or, can I cut the boring part and just say, B. “Gosh, it was like an orgasm—wasn’t it—when Biden said, ‘My whole soul is in this: bringing America together, uniting our people and uniting our nation?’”

Quickly now, please. Comment below. Our union needs to start, like, yesterday. A or B.

Grammar at the Edge of the Envelope

“Pilots are so much better than everyone else,” thought a young boy once. As a grown man, I think we should all agree with the boy. A few years ago, I found a spare moment hidden in Iraq of all places. That moment contained irrefutable proof that pilots are better than everyone else. Pilots are better because they live many lifetimes, while other people only live one lifetime. Confusing? Maybe it’d help if I said that pilots are better because they live many mini-lifetimes. Any better? No? Allow me to explain.

A mini-lifetime is the term I use to capture the three-part event of flight: takeoff, flight, and landing. In order for the definition’s perfection to become perceivable, you must understand that a lifetime has three key parts: birth, life, and death. To critical readers, I confess that there certainly are other professions or human activities that contain just three parts; however, I’m convinced you’ll see there is a special genius in this metaphor’s specific use of pilots.

To begin the comparison, birth and takeoff share a foundational similarity. Both initiate a sequence of events that will only ever come to an end. Next, life and flight are that sequence. They are the continuation of birth and takeoff. Moreover, during life and flight, no matter how a person lives or how a person flies, a tragic end lingers at a moment’s distance. Finally, the death (near death, at least) and landing phases offer a unique ability to look back over the life and flight phases with the express purpose of forming judgments. For pilots, these judgments, of course, are not the end–but the beginning. The end is the application of the lessons learned. Note, that pilots repeat this three-chapter cycle almost daily. And while doing so, they become very proficient at improving their flying skills through the post-landing debriefs. Grounded folk, on the other hand, are not afforded these vantage points. They must make extreme efforts to be still, take inventory, determine lessons learned, and then apply the lessons as they resume living out their lifetime. Consequently, pilots living all these mini-lifetimes–do not discount the very real threat of death this metaphor demands–are in the habit of debriefing their own grounded lives each day, week, month, year, or whatever time period and applying the lessons learned to the next iteration. That is why they are better.

Whew! Glad you’re still with me, as I have great news. That was just the introduction. Let’s not kid ourselves, it was worth it. Next up, the part of the assignment you’ve been waiting for: more meta-for. (Yep, that’s my humor.)

The assignment was to write a(n interesting) paper relating grammar to some other system in life. Naturally, it follows that if my flying-life metaphor is so perfect, grammar being a part of life, then grammar should be able to be explained via flying. As Rafiki tells newly-mature Simba in the Disney classic, The Lion King, “Eet is time.” It is time to push the metaphor further.

Clear as day, the first requirement for grammar is words. Lady Luck, beauty that she is, smiled down on me as it became clear that flying also needs one thing more than anything else: pilots. So words must be pilots. Obviously, humans don’t have physiological wings, so we invented machines that could lift us into the air. Just as all humans are not pilots, all sounds humans emit are not words. Within the sounds that can be classified as words, there are subtle intonations and pauses. When creating written language, earlier man decided these subtle intonations and pauses required special written markings, different from alpha characters. Whatever name initially given, today we call them punctuation. Like a pilot’s aircraft, punctuation is a tool to help words achieve their God-given purpose. A pilot’s purpose is to accomplish a mission and he does so using an aircraft. A written word’s purpose is to accomplish communication and it does so using punctuation.

With words and punctuation under my belt, I pressed onward. What more could I synthesize? I knew that individual words and punctuation didn’t communicate as well as a group of words, a sentence, does. Equivalently, pilots and aircraft don’t accomplish missions in a single action–they need a group of actions. So a sentence, then, is the coordinated cycle of takeoff/flight/landing. Each takeoff is the capital letter and marks the beginning of an independent, complete thought. The flight is that thought. And the landing is the concluding punctuation. (This is pretend world. It’s okay if the punctuation is both the aircraft and the landing…think how a period can be both part of an ellipses and a period at the same time if you need to.)

But wait! Stop here, and consider a new revelation. Consider how an exclamation point has varied tones. I said consider how an exclamation point has varied tones, silly! Then consider how a perfect landing would be a soft, beautiful exclamation point as in, “Man, that landing was as sublime as an outdoor professional hockey game being graced by light falling snow!” While a crash landing would be a hard, abrupt exclamation point found in, “Bam!” At first daunting, the question mark still fits the metaphor. Can you picture a student pilot attempting to land a helicopter? Sometimes the student thinks he has landed just once, when the instructor knows it was at least twice. After all, there is no place to record number-of-times-student-bounced-the-helicopter-before-finally-landing, is there?

Next, while it is possible that a mission can be comprised of just one takeoff/fly/land iteration, most missions include several such iterations. Similarly, it is true that some sentences can be paragraphs themselves. A more elementary view is that sentences need other sentences in order to be a paragraph. A paragraph is usually a more effective method of communication than a sentence or word. This, then, is the same as how missions containing several iterations of takeoff/fly/land are usually more effective missions. Specifically, if a pilot flies to a destination to pick up someone, flies to a second destination to drop them off, and then flies back to the home airfield, that is more effective than just one of those three iterations. One effective mission composed of three total flights.

This metaphor becomes ever easier as we move away from the basics, into the more subjective parts of written language. Lexicon, or an individual’s dictionary, would be the capabilities of a particular pilot, whereas diction would be his or her style. Metadiscourse, or the words and phrases that help the reader understand the writer’s meaning, would be a pilot’s clothing. Is the pilot wearing a uniform, or just dressed in plain clothes? Just as a writer’s intentional metadiscourse helps the reader understand the writer, a pilot’s clothes conveys who the pilot works for, how good he or she is, how experienced he or she is, and what type of missions the pilot accomplishes (passenger transport, combat, reconnaissance, etc.).

In the end, this assignment is over before it begins. That grammar can be synthesized into any system shows that it can be synthesized into every system. That’s because grammar is a system. That’s the point, isn’t it? The real trouble for sticklers of grammar, however, is not that people don’t use the system; it’s that life goes on whether people use or ignore the system. This, just as life goes on whether or not human flight occurs. If there is any overarching lesson this metaphor can teach us, it is that grammar is not a solution to a problem. It is a tool to be used by those who care to use it. Just like flying.